Yoga is the human quest for remembering our true nature, our deepest selves . Since the dawn of recorded time human beings have sought to transcend the human condition, to go beyond ordinary consciousness . Basic questions such as Who am I? and Why am I here? have driven mankind’s spiritual pursuits for millenia . In every human heart lies a deep longing to connect to something bigger than oneself, to find a sense of belonging and meaning to life . At the core of this longing is a basic human desire for happiness that transcends culture and time . Every human being wants to find happiness .

This quest for happiness is not so much a striving to acquire something that exists outside of us as it is an innate desire to remember something that is part of our very nature. First and foremost, yoga is about remembering ourselves, our own deepest purpose for being. The journey of yoga is an inner journey to the very essence of our existence. The message of yoga is that the nature of that inner essence is happiness or bliss (ananda in Sanskrit). The search for happiness within every human heart is the search for the true nature of who we are.

This quest for happiness is not so much a striving to acquire something that exists outside of us as it is an innate desire to remember something that is part of our very nature. First and foremost, yoga is about remembering ourselves, our own deepest purpose for being. The journey of yoga is an inner journey to the very essence of our existence. The message of yoga is that the nature of that inner essence is happiness or bliss (ananda in Sanskrit). The search for happiness within every human heart is the search for the true nature of who we are.

Nowhere on earth has the impulse to transcend the human condition been more consistent and creative than in India—home to an overwhelming variety of spiritual beliefs, practices, and approaches designed to help the spiritual seeker achieve higher levels of consciousness. The practice of yoga is deeply woven into the rich Indian culture and evolved from the same roots as many other spiritual practices. As an ancient science, it was designed to facilitate the seeker’s inner journey to a higher level of being.

Though the art of yoga is often associated with Hinduism, yoga is not a religion. While a religion emphasizes belief structures about life and the human relationship to the divine, yoga seeks to reveal our own deepest nature through direct experience of our divinity. One need not be religious to practice yoga, nor does yoga exclude any religious practice. All that is required to practice yoga is a desire to learn more about yourself and your relationship to the universe.

The Sanskrit word yoga means “union” or “yoking” and has been defined as the union of mind and body, heart and actions. The type of yoga that most Westerners recognize is the series of physical postures, or asanas, that strengthens and makes the body more flexible. This form of yoga is referred to as hatha yoga. But hatha yoga is much more than just a physical practice. The word hatha is a Sanskrit combination of the word ha (sun) and tha (moon), which is itself a union of opposites. Qualities associated with the sun are heat, masculinity, and effort, while moon qualities are coolness, femininity, and surrender. Hatha yoga is designed to help us bring pairs of opposites together in our hearts, minds, and bodies for the purpose of discovering something deeper about the nature of our existence. These opposites have been referred to as stepping stones on a path of grace. They are qualities of heart such as effort and surrender, courage and contentment, stillness and playfulness. They may also be physical qualities such as hard and soft, hot and cold, solid and flowing. In essence, the practice of yoga brings together apparent opposites into a harmonious union—a place in the middle.

This middle place is a gateway into a whole new world for most of us. It is a place where we discover wonderful new things about our abilities and possibilities for our lives. It is a gateway into our own hearts. When we step through this gateway we do not step alone. We find before us the footprints of many who have gone before and illuminated the path. We find ourselves in the current of a great river that has carried the hopes and dreams of many seekers over the centuries. There is power in the river that will help us along our own spiritual journey, the power of grace. And by stepping through that gateway into the currents of grace, the yogi steps forward into ever-greater possibilities of his or her own happiness and self-expression.

Roots of Yoga

The earliest recorded form of yoga was a deeply introspective and meditative practice that focused on sacrificial rituals. Yoga is first mentioned in the Vedas, a body of four sacred texts that are the oldest and most treasured scriptures of the sacred canon of Hinduism. It is in the oldest of these scriptures, the Rg (pronounced rig) Veda, where the word yoga and its root, yuj, which means “yoke,” first appear. However, at that time no systematic path of yoga yet existed.

Most scholars believe the Vedas were composed by Sanskrit-speaking people who arrived in the Indus Valley of what is now India somewhere between 1800 and 1500 b.c.e. It is not clear whether these people, calling themselves Arya, invaded or peace- fully assimilated the prevailing culture into their own, but they brought with them the earliest roots of what we now enjoy as the practice of yoga.

Veda means “knowledge” or “wisdom,” and the original four texts are regarded as sacred revelations to the ancient seers (called rishis). They consist of literally thousands of verses of hymns and sacrificial chants designed to bring order and good fortune to those who invoke them. Two more texts, the Brahmanas (1000 to 800 b.c.e.) and the Aranyakas (800 b.c.e.), followed.

The Vedas and their commentaries were essentially how-to guides for ritual and sacrifice. They gave people instructions on how to make their lives better and attain success in marriage, business, war, and so forth. If you wanted to ensure success during Vedic time you would hire a priest to perform a ceremony from one of the Vedic texts.

At the end of the Vedic period (about 600 to 550 b.c.e.) there was an evolutionary leap in yogic thought with the appearance of the Upanishads. The Upanishads went beyond the instruction manual approach of the Vedas to ask the deeper questions about the meaning of a spiritual life.

The word upanishad comes from the prefixes upa, (approach), and ni, (near), and the verbal root shad, “to sit.” It literally means “to sit nearby.” The Upanishads serve as an invitation to come and sit near a teacher who can impart the wisdom of deeper understanding to the student. It was customary in Vedic times for students to gather around at the feet of their teacher and learn his wisdom by heart. But the Upanishads raised the bar for the inquiry into the mysteries of life beyond that of the Vedas. In the words of Douglas Brooks, Tantric scholar and professor of religion at the University of Rochester, the Upanishads were for those who wanted to “stay after school,” to go deeper and ask not only how the universe works but why does it work the way it does, what is its essential nature, and what is my place in it?

For fear of whom fire burns, for fear of whom the sun shines, for fear of whom the winds, clouds and death perform their offices? Tattrirya Upanishad

It is the deeper inquiry of the Upanishads that defines the evolutionary path to the yoga that we know today. Over the centuries the Upanishads became the sustaining original wisdom of all great yoga traditions.

The early centuries before the Christian era were rich in the development of Indian thought. Near the time when the Upanishads were being composed (or slightly later) the legendary sage and scholar Patanjali was compiling his list of Yoga Sutras. The word sutra is composed of two parts, su, meaning thread and tra, meaning to transcend. The Sutras are like pearls on a thread that helps the student to transcend. They are the threads that weave together the teacher, the teaching, and the student. The Sutras were composed as a list of aphorisms boiling down the yogic wisdom of the age into concise sentences that could easily be committed to memory. Their terse nature left them open to interpretation, leading to a long period of commentary and analysis that continues to this day. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras became the cornerstone in the system known today as Classical yoga, which is explored in greater detail in the next section.

Three Yogic World Views

In the West, yoga is often confused with Hinduism. It is understandable that people group the two together because they share a common culture, language, and terminology. Both traditions trace their roots back to the Rg Veda. The common basis for both traditions is the Sanskrit language. In India many Hindus practice yoga, but not all yogis are Hindu.

Yoga is a philosophical system that prescribes a way of life and is actually just one of the philosophical schools recognized by Hindu orthodoxy as a valid repre- sentation of Vedic truth. There are many such schools that have played a role in the evolution of Indian thought. Each school is a form of philosophical thought that has evolved in India throughout the centuries. Several of these systems have been exported to the West, and particularly the United States, over the years. With the recent, unprecedented rise in the popularity of hatha yoga it is important to identify the foundations on which modern yoga systems are based.

Among the exports of Indian thought, three philosophical traditions now form an essential core within contemporary yoga: Classical yoga, Advaita Vedanta, and Tantra. Every popular system of hatha yoga in the West today is grounded in the philosophy of at least one of these three schools. The work of Tantric scholar Douglas Brooks discussed next provides a foundation for understanding these three systems.

Classical Yoga

Classical yoga is the name given to those schools of yoga that consider themselves the most authentic representatives of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. It is a dualistic philosophy that draws a clear distinction between the two major “substances” of the universe, prakriti (matter) and purusha (spirit). In Classical yoga matter and spirit are qualitatively different realities that never mix or join together. Spirit is absolute, unchanging, and superior to matter. Matter is relative, changeable, and inferior to spirit.

The essential nature of human beings is pure spirit, while everything in the physical world, including emotions and thoughts, is considered material. Human suffering is the result of confusing one’s true nature with this lesser, material reality. The goal of Classical yoga is to separate these two realities, to extract one’s true nature from the body/mind. It is designed to help students experience their immortal spirits. The goal of the yoga practice is to get into the body so you can get out of it. Sometimes these practices include harsh discipline that requires students to push beyond the pain in order to realize that they are something other than their bodies or their feelings. Because the body is inferior, it must be disciplined into submission so that spirit may be realized. If you are in a yoga class with a Classical yoga influence there will likely be a strong emphasis on controlling the body and mind through discipline. You may hear phrases like “push through the pain” when the postures become especially challenging.

For the Classical yogi the body and this physical life are problems to be solved. Birth is the result of a failure to realize our true nature in a previous life, and we are sentenced to come back again and again until we realize the truth. Freedom from the prison of embodiment comes when the seeker isolates the experience of pure spirit from the lesser realities of body, mind, and thoughts.

Advaita Vedanta

Vedanta means “conclusion or end of the Vedas,” because this method is based on the last set of Vedic texts and teachings, the Upanishads. In contrast to the dualistic philosophy of Classical yoga, Advaita (nondual) Vedanta negates the concept of separate realities for matter and spirit. In Advaita Vedanta only spirit is real; matter is an illusion. Our experience of matter, our bodies, our thoughts and feelings, and embodied life itself are an error in perception that can be corrected. There is only one true reality, but it appears as many to the unenlightened mind. This reality is unchanging and constant. Anything that changes, therefore, must be unreal. Since there is only one reality, all difference, as we perceive it in our worldly experience, simply does not exist. If we have a favorite flavor of ice cream or color of the rainbow it is simply an error of judgment. No perceived differences are real. All human suffering comes from this error of perception.

For Vedantins, like Classical yogis, this embodied life is a problem to be solved. And the Vedantins, too, have a solution. One of the primary strategies for overcoming erroneous thinking is referred to as neti, neti (not this, not this). The practice is to repeat phrases like “I am not my body, for my body changes,” “I am not my mind, for my mind changes,” “I am not my emotions, for my emotions change.” Disciplined application of this approach is designed to bring true knowledge that will dispel the error in thought. Once the seeker acquires true knowledge, he or she becomes enlightened. An enlightened one may continue to inhabit the body but will have the awareness that the body, thoughts, and everything seen are just illusions. If you are in a hatha yoga class with an Advaita Vedanta influence you may hear phrases like “you are not your body” or “you are not your thoughts.”

Tantra

Sometime around the fifth or sixth century b.c.e. there was another revolution in Indian philosophical thought regarding the nature of the universe and our relation- ship to it. It was a radical shift that gave rise to a body of texts, oral traditions, and practices known by the name Tantra, meaning “loom” or “weave” (also called agama, meaning “testimony”).

Rather than join the argument between Classical and Advaita Vedanta yoga con- cerning the nature of matter and spirit, the Tantras transmuted it by agreeing with both sides and adding a new twist. Like Classical yogis, the Tantras affirmed the existence of spirit and matter; however, neither was granted supremacy. Like Advaita Vedantans, they affirmed the supreme unity of all reality. How could this be? How could both of the previously dominant philosophies be true at the same time?

Tantric philosophers resolved the issue with a masterful weaving together of these two great teachings. In essence they chose radical acceptance of all reality, both spiritual and material. The physical universe is explained as a diverse manifestation of the one supreme reality of divinity. The grounding matrix of physical reality (prakriti to Classical yogis) is the Vedantic supreme self. The world we live in is the manifestation of infinite forms of this supreme consciousness.

This was an incredible shift in the prevailing views, which considered the physical body as a problem to be solved and required self-denial and intense discipline of the physical body in order to either rise above it (Classical) or realize it as illusion (Advaita Vedanta). In bold contrast, the followers of Tantric philosophy considered the body as a manifestation of divinity itself, worthy of celebration and honor, rather than the result of a mistake or failure from a previous lifetime. This viewpoint was nothing less than a radical acceptance of the body and all of life as divinity incarnate. Suddenly there was nothing to renounce and no failed past life causing one’s current birth, only the choice of living fully in the reality one has received as a divine gift.

In contrast to the Classical and Advaita Vedanta adherents who renounced the world as inferior or illusion, the followers of this new path were primarily lay people. They were heads of households and businessmen living in the everyday world, earning their living and paying their bills. Tantric scholar Douglas Brooks has coined the term rajanakas to refer to this group. The term rajanaka means “sovereign over one’s own life”; it indicates that these yogis used their practice to gain mastery over all aspects of their lives while still living in the secular world. The modern day yoga school is based on the Rajanaka Tantra tradition and draws upon the rich Tantric philosophy without the use of ancient Tantric ritual.

Needless to say, this fundamental shift toward Tantric thought affected the yogic practices of the day and continues to highlight the differences in the prevailing hatha yoga systems in the West. If you enter a yoga class based on Rajanaka Tantra philosophy you will likely hear phrases like “open to grace,” “your body is a divine temple” and “shine out from your heart and express the divinity within you.”

Eight Limbs of Classical Yoga

As outlined earlier, the Classical yoga viewpoint follows a strict interpretation of the Yoga Sutras—the culmination of a long development of the science of yoga that set forth a very specific path to enlightenment. There are eight component stages, collectively referred to as Ashtanga yoga (ashta, “eight” and anga “limb”), the eight-limbed path to mystical union. The stages begin with a set of ethical codes and progress through physical postures, breathing exercises, and mental practices, culminating in the highest stage of absorption in the absolute.

Here is a description of the eight limbs:

1 . Yama. Five virtues, or restraints, that govern our relationships with others and the world: ahimsa (noninjury), satya (truthfulness), asteya (nonstealing), brahmacharya (Godlike conduct), and aparigraha (nonclinging).

2 . Niyama. Five observances of one’s own physical appearance, actions, words, and thoughts that govern our relationship with ourselves: shauca (purity or cleanliness), santosha (contentment), tapas (heat, burning desire for reunion with God), svadyaya (self-study or self-inquiry) and isvara pranidhana (devotion or surrender to the Lord, “thy will be done”).

3 . Asana. Postures for creating firmness of body, steadiness of intelligence, and benevolence of spirit. The physical practice most familiar to Westerners as yoga.

4 . Pranayama. A set of breathing exercises designed to help the yogi master the life force.

5 . Pratyahara. Withdrawal of the senses, mind, and consciousness from the outside world; focus inward on the self.

6 . Dharana. Focused concentration. With the body tempered by asanas, the mind refined by the fire of pranayama, and the senses under control using pratyahara, the student reaches this sixth stage.

7 . Dhyana. Meditation. Withdrawing the consciousness into the soul.

8 . Samadhi. Ecstasy. Merging with the divine. Self-realization. One experiences consciousness, truth, and unutterable joy. One must experience samadhi in order to understand it, because it is beyond the mind.

The system of Classical yoga based on the Yoga Sutras has undoubtedly been the most common style of yoga taught in the West. It holds a strong appeal for students who want a well-defined, stepwise approach to their spiritual advancement.

Paths of Yoga

Just as there are distinct philosophies and interpretations of the scriptures in world religions, different philosophies have formed in the world of yoga. Accordingly, the living science of yoga has been organized into many different paths or approaches over the centuries. It is no surprise that human beings, with so much diversity of thought and feeling, would find so many paths to their spiritual development in the realm of yoga. Yet, like many different paths to the top of the same mountain, all paths lead to the same goal. Many people find that, as they progress through their lives, more than one path speaks to their spiritual needs. The best yoga paths for you are simply the ones that appeal most to your heart.

There are a number of recognized paths of yoga, of which six have gained prominence in the Hindu culture of India: bhakti, jnana, karma, raja, mantra, and hatha.

Bhakti yoga is the yoga of devotion. It emphasizes the opening of the heart to divine love, the union of lover (the yogi) and beloved (the divine). This devotional love is often translated into song or chanting, with ecstatic repetition of the names of the beloved, in gatherings called kirtans. One of the most popular kirtan artists in the United States today is Krishna Das, who is a bhakti yoga practitioner.

Jnana yoga is the yoga of wisdom. Jnana means “knowledge.” This is a path of self-realization through the exercise of discerning the real from the unreal or illusory. It is a practice of discriminating between the products of nature and the transcendental Self, until the true Self is realized in the moment of liberation. This is a strictly nondualistic (Advaita Vedanta) path that requires the seeker to separate the real from the unreal, the Self from the non-Self. Since the mind is considered part of the unreal, one must use the mind to outwit the mind. The principle techniques of this path are meditation and contemplation.

Karma yoga is the yoga of selfless action. Karma means “action.” The karma yogi makes all actions an offering to God, with no thought of personal gain. Through serving others one is selflessly serving God. Mother Theresa and Mahatma Gandhi are examples of karma yoga practitioners.

Raja yoga is the “royal” yoga. Raj means “king,” and raja yoga seeks to reveal the king within each of us that is normally hidden by our everyday actions and concealed by the workings of the mind. Raja yoga is a Classical yoga path most often associated with Ashtanga, the eight-limbed path of Patanjali. For the raja yogi the Sutras serve as an instruction manual to one’s own experience of reality.

Mantra yoga is the yoga of sound. The word mantra comes from the root man, “to think” and the suffix tra, “suggesting instrumentality.” So a mantra is a thought or intention expressed as sound. A mantra is a sacred utterance or sound charged with psychospiritual power. Yogis use mantras to achieve deep states of meditation and to invoke specific states of consciousness, and they believe that a mantra expressing a particular aspect of the divine will help to awaken that aspect of their own conscious- ness. For instance, a mantra to Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, is used to help awaken that part of our personalities that can overcome the obstacles in our lives. The most recognized and important mantra is the sound OM.

Hatha yoga is called the forceful yoga and is defined in previous sections. There are many schools of hatha yoga, each rooted in one of the major philosophical traditions mentioned earlier (Classical, Advaita Vedanta, or Tantra). Many styles of hatha yoga have become popular in the West ranging from healing therapy to vigorous athletic flow. Some schools work with detailed physical alignment while others focus only on the inner experience. You may practice yoga in air-conditioned comfort or in temperatures of 100-plus degrees Farenheit (38+ ºC). There is no shortage of variety and you are sure to find a style that agrees with you.

Energetic Anatomy: The Chakras

The practices of yoga are designed to deal with our bodies on more than just a physical level. To the yogi the physical body is a manifestation, a reflection, of the astral or energy body. This body of energy has its own anatomy, based on seven major energy vortices called chakras. The word chakra means wheel or disk. The chakras line up along a central energy channel, or nadi, which runs from the base of the spine through the top of the head. It is called the sushumna. The sushumna is the energy body’s primary pathway for the life force (kundalini). The chakras are nodes of connection along this pathway where other energy channels intersect. The goal of classical yoga is to awaken the kundalini energy that lies dormant at the base of the spine and make it rise to the highest energy vortex at the crown of the head. The Tantric approach is to stir one’s awareness of that divine energy which is already awake. The yogi who can achieve and maintain this state is considered enlightened.

There are approximately 72,000 nadis in the energy body that channel energy. Three are primary, including the central sushumna and two others on either side. The left-side channel is called the ida. Its qualities are cool, soft, reflective, and sensitive, like the moon. The right-side channel is called the pingala and is associated with heat, activity, and strength, like the sun. The balance of energy flow on these two sides affects the sensations of heat and cold in the physical body. These two channels originate in the sushumna, near the base of the spine (in an energy vortex, or bulb, called a kanda), and they correspond to the first chakra, muladhara. They spiral up the sushumna, crisscrossing at each of the six higher chakras.

The chakras can be visualized from the front of the body as lotus flowers with the roots in the back. As the life force, or prana, moves through the system, it makes the chakras spin. The health of this system of energy flow depends on the chakras spinning at a proper speed. If the chakras spin too slowly, too weakly, or too fast, this creates a damming effect for the energy flow, and the system becomes imbalanced, which can manifest as emotional and physical illness.

Each chakra has a physical location in the body and is associated with physical, emotional, and energetic characteristics. Additionally, each chakra is associated with basic human rights and how we feel physically and energetically. For instance, if a child knows that he is loved, honored, and respected by his parents, he can develop a healthy sense of security. As a result the functioning of his muladhara chakra, which is associated with security, is enhanced.

The chakras can serve as a type of energetic health monitor for the student of yoga. As we perform the physical practice of hatha yoga we increase the health, awareness, and energy flow to each section of our bodies. If a particular section of our body is functioning at optimal levels energetically, the chakra associated with that section will also function optimally. Therefore, a hatha yoga practice can be designed to increase a student’s self-esteem by strengthening the “band of self esteem,” the region of the manipura chakra (the waistline).

Energy Gates: The Bandhas

Bandhas are a series of energy gates in the subtle energy body that regulate the flow of psychosomatic energy. The word bandha means lock, or constriction. You can think of the bandhas like the one-way valves in your circulatory system. These valves allow blood to flow in one direction as the heart pumps but not to reverse its flow on the upstroke, ensuring proper direction of blood flow. The bandhas direct the life force in a similar way.

Yoga practitioners learn to tone certain sets of muscles in order to provide a lock, or closure, that holds psychosomatic energy and moves it powerfully through the subtle energy channels. This generates a psychic heat in the subtle body that helps to stimulate the awakening of the kundalini energy.

There are three primary bandhas in the body:

Mulabandha—the root lock—is located at the base of the spine. It stops the down- ward flow of life force, apana, so that it can be equalized with the upward flow, prana. The physical location of mulabandha is the perineum (the soft tissue between the anus and the genitals). Mulabandha comes as you draw energy through the muscles of the perineum toward a central point, creating an energetic lift through the core of the body. It is often difficult for beginners to access these muscles until they have increased their body awareness in this area. Such aware- ness can be increased by engaging the pelvic floor muscles as you would to stop the flow of urination. With heightened awareness mulabandha can be practiced by drawing energy through the muscles of the perineum toward a central point, creating an energetic lift through the core of the body.

Uddiyana bandha. Uddiyana means “flying upward.” This “gate” is located in the low abdomen. Uddiyana bandha is performed by exhaling fully and drawing the lower abdomen in and up while simultaneously lifting the diaphragm. It is important not to engage this bandha after eating or during deep inhalation, as it puts pressure on the stomach, lungs, and other internal organs. This bandha is intended to create further lift for the upward flow of prana in the sushumna.

Jalandhara bandha—chin or throat lock—is located at the top of the throat. This lock stops prana flow from leaking upward out of the torso and downward from the head into the torso. Jala means “net,” “web,” or “mesh.” This lock is performed as follows: While lengthening your neck, curl your head back initiating the movement from the palate as if drinking sweet nectar. Keeping your neck extending upward, release your head forward like the bow of a swan, taking the top of your throat back and up as if your throat were smiling from ear to ear. Continue the release of your chin toward your chest while taking the top of the throat back and up.

Performed together, these bandhas create an energy container between the floor of the pelvis and the throat chakra. The psychic heat generated helps to mobilize the upward rising of the kundalini energy and clear blockages in the central energy channel.

When you attend a hatha yoga class you may be taught how to use the bandhas by the specific names referred above. Or you may not hear the word bandha mentioned at all. Some schools of hatha yoga teach bandhas most of the time, while others teach them sparingly but some schools use alignment principles to create the same effect.

This article follows the latter approach for teaching asanas. Mulabandha is engaged by the following sequence of instructions which are common to many asanas in this sextion —move your thighs back; widen your pelvic floor; keeping that action, tuck your tailbone down and under; and extend from your low belly up through the top of your head. Uddiyana bandha is engaged by the following instructions—draw the flesh below your navel in and up (take the sides of your waistline back) and extend from your low belly up through the top of your head.

Using Drishtis

A drishti is a gaze, or a point of focus. Drishtis are included for each pose in other articles of this site as a way to direct your focus when you practice. Dristhis are actually intended to direct your “inner” focus more than your physical sight, even though the directions may be to fix your gaze on an external object or a point on your body, such as the floor, the tip of your nose, or your navel. Dristhis are designed to help you practice your yoga with awareness and without being distracted by your surroundings.

Getting the Most From Your Yoga Practice

Now that you have been exposed to some of the history and philosophy of yoga, let’s introduce some of the basic elements to consider in your yoga practice. Simple choices you make about clothing, time, your place of practice, and the use of props can make all the difference in your enjoyment and make the time you spend practicing yoga most effective. Learning how to use your breath during yoga is highly important to enhance your practice and make your practice the best it can be for you. You will likely find that meditation is a wonderful complement to your practice of yoga and an equally powerful stand-alone practice that you will enjoy for years to come. All of these practices will be introduced in the sections that follow so that your yoga toolbox will be well stocked when you begin your practice of hatha yoga.

Yogic Breathing

Our breath is synonymous with our life. Breathing is so natural and automatic that most people never even notice that they are breathing unless it is excited or restricted in some way. Life enters us with our first inhalation and leaves with our final exhalation. It is truly one with our life force. The animating life force of the breath can be thought of as the play of a divine goddess, called Shakti. Shakti is the creative energy of the divine that animates everything in the universe. In essence we are always being breathed by this divine energy. When we inhale the Shakti is exhaling into us, and when we exhale it is her inhale.

For the yogi the breath serves as an extension of the prana, or life force, as it moves in the body. It is the physical manifestation of the natural flow of this energy.

It is the medium through which we express the attitude in our hearts and translate it into the outer body. By using the breath we increase our sensitivity to the flow of energy, and with that increased sensitivity we are closer to realization of our own divine nature. The breath has the capacity to open the body and allow our energy to flow more freely in our yoga practice. Awareness of breath brings a mindful, sacred quality to an asana practice.

One of the first lessons to learn in the practice of yoga is proper use of the breath. Yoga is a practice of connecting to the deep spirit within each of us. It is the practice of tuning in to the essence of our hearts, all of our dreams and desires, and expressing them joyfully through our physical bodies. The breath is the medium through which we make that connection.

The Natural Breath

When we are born, our breath is full, flowing, and uninhibited. Our bodies and minds are designed for the fullest expression of the breath. We don’t have to think in order to breathe in that way. This type of breath just happens with no conscious effort on our parts. This has been referred to as “the natural breath” for which there are several key characteristics:

- The pelvic floor expands and descends on inhalation and contracts and lifts on exhalation.

- The collarbone lifts and rolls upward on inhalation and descends on exhalation.

- The upper arms externally rotate on inhalation and internally rotate on exhalation.

You can see this process most clearly in the breathing of a baby, whose belly will rise and fall with each breath. Babies seem to breathe with their whole bodies, as if every part expands and contracts with the movement of the breath. You can observe your own diaphragmatic breathing by lying on your back and noticing the natural rise and fall of your belly with the breath.

The natural breath wants to flow in us as the fullest possible expression of the Shakti energy. However, if mental or emotional traumas are introduced we may learn different breathing habits that restrict this natural flow. For instance, when we are threatened or upset our whole body tightens we enter a state commonly referred to as the fight-or-flight response. In such a state we are reduced to our basic survival instincts—the abdomen tightens, restricting diaphragmatic breathing, and quick, shallow chest breathing results. This state might be healthy for a person who has stepped in front of a bus. However, chronic exposure to circumstances that elicit the fight-or-flight response can cause a person to form long-term restricted breathing habits. The emotional stresses of a fast-paced lifestyle can cause a

person to lose touch with the fullness of his or her breath. It is not uncommon forWesterners to use only a small percentage of our breathing capacity. Returning to an awareness of our natural breath can help us to recover our healthy breathing patterns.

Uninhibited breathing creates the natural rise and fall of the belly because of the movement of the diaphragm, the main muscle responsible for breathing. The torso of our bodies is divided into two main cavities—the thoracic, or chest cavity, and the abdominal cavity. At the bottom of our chest cavity we have a muscular membrane called the diaphragm, which completely separates these two cavities. Like the head of a drum stretched across the bottom of our rib cage, the outline of the diaphragm is roughly the outline along the base of the ribs. It attaches to the bottom of the sternum (the center chest, where the ribs attach) and follows the lowest outline of the ribs all the way back to the lumbar spine, where it attaches via tendinous tissues called crura. There are three openings in the “drum head” of the diaphragm to allow descending and ascending blood to flow and food to pass. The heart rests just above the diaphragm, and the digestive organs are just below it. The lower surfaces of the lungs are attached to the upper surface of the diaphragm.

As the diaphragm moves through a large range of motion it substantially changes the volume of the thoracic cavity. The muscles of the rib cage and upper chest also change thoracic volume, although with much less efficiency than the diaphragm.

When we breathe naturally the diaphragm moves down to create a vacuum in the chest cavity that draws the air into the lungs. Because the downward movement of the diaphragm displaces the organs of the abdomen, the belly naturally distends on inhalation and retracts on exhalation as in the natural breath. You can increase your awareness of your diaphragm by placing a small, soft weight, such as a bag of rice or beans, on your abdomen between your ribs and your navel. As you inhale, notice the work that the diaphragm must do to lift the extra weight. As you exhale, let your belly gently fall under the weight. Simply increasing your awareness of your natural breath, without trying to manipulate or control your breathing, can bring you to a state of peace and relaxation.

Diaphragmatic Breathing

A yogic practice that consciously uses the diaphragm with the breath is called diaphragmatic breathing. The following exercise is a remedial form of diaphragmatic breathing that helps to counter those problems that interfere with the natural breath.

Begin the exercise in a reclining position with your spine resting on a stack of blankets. Fold three firm-weave blankets (Mexican blankets work well) lengthwise to a width just less than the width of your shoulders and to a length just longer than the distance from your navel to the top of your head. Stack two of the blankets one on top of the other. Stack the third blanket crosswise to the other two atone end of the stack. Sit on the floor in front of the stack, and lie back with your head resting on the third blanket such that your head is slightly elevated. From this position you can easily practice breathing into the three regions of your torso, as follows:

Lower belly: Place your hands on your low belly, just above the navel, with the tips of your middle fingers touching. Breath with your diaphragm so that your belly rises into your hands and your fingertips separate slightly. Also allow the breath to fill the side and back belly region so that there is a full expansion in all directions. As you exhale allow the lower torso to contract so that your fingers come back into contact. Practice several breaths in and out of the low-belly region of your torso.

Mid-chest: Place your hands on the sides of your rib cage and apply a slight inward pressure to your ribs. As you inhale, in addition to lifting the low belly, consciously expand the sides of your rib cage to make more room for the breath. Notice how the ribs both expand into your hands and separate slightly from each other. Continue this breathing practice for several breaths.

Upper chest: Place your hands on your upper chest with your index fingers rest- ing on your collarbones. Breathe into your hands by filling your upper chest with your breath and notice the expansion upward into your hands. You will notice the least amount of movement into this region even as the amount of effort is substantially greater.

Full Yogic Breathing

The next step in a yogic breathing practice is to learn full yogic breathing. This technique also uses all three areas of the torso to allow the fullest breath possible with two significant changes from diaphragmatic breathing: 1) With full yogic breathing as you inhale, you tone the muscles of your low abdomen so that your torso expands to the side with your breath rather than having your belly rise; 2) on exhalation, you keep your ribs expanded (as if you are inhaling).

To practice full yogic breathing in the reclining position repeat the three steps described for diaphragmatic breathing within the duration of a single breath. On inhalation keep the low belly toned so that your belly does not rise. As you exhale, keep your chest expanded and full and empty the air from top to bottom. Keep your breath smooth and steady, and attempt to make the duration of the inhalation and exhalation the same. You may discontinue placing your hands on your torso once you have learned the technique. Once you’ve mastered this breathing in the reclining position, you may attempt it in a sitting position. For this practice, keep your pelvis heavy on inhalation as you breathe into all three torso regions successively. On exhalation, keep your ribs lifted and expanded.

Other Breathing Techniques

Over the centuries yogis have understood the power of the breath to alter states of consciousness and have developed breathing techniques to create a desired state. These techniques of the breath are called pranayama.

It is interesting to consider the use and interpretation of these breathing techniques from the perspective of the major yogic schools. Some Classical yogis translate pranayama as “breath control,” a combination of the Sanskrit terms prana, or life force (breath), and yama, “control” or “restriction.” This interpretation makes sense from the Classical perspective that the body is inferior to spirit and is to be dominated or forced into submission so that we can realize our true nature. In another interpretation the body and the breath are seen as manifestations of divinity. Accordingly, pranayama is interpreted as prana and ayama, which means “noncontrol.” From this perspective the techniques are seen as a way of skillfully participating with the breath, or dancing with the divine goddess Shakti.

There are a wide variety of breathing techniques that have been developed, depending on the desired state the yogi wishes to attain. Two of the most common pranayamas are described below.

Ujjayi Breathing Ujjayi, which means “victoriously uprising,” is the most common yogic breathing technique. You will hear the sound of ujjayi breathing in almost any yoga class. It is created by toning the epiglottis to intentionally create a sound at the back of your throat. The sound has been compared to the whispered sound of haaa in the back of your throat as you breathe. It creates a direct feedback that yogis use to monitor the flow of their breath. The quality of your breath is directly related to your state of mind, so when you are aware of your breath you can be aware of your inner state.

To practice ujjayi breathing take a deep inhalation followed by a deep exhalation, to open yourself up to receive the breath. Inhale through your nose as you slightly constrict the muscles in the back of your throat to create a whispering sound. Exhale through your nose creating the same sound. Keep the flow of your breath even and smooth from the beginning to the end of each inhalation-exhalation cycle. Generally we inhale and exhale faster at the beginning of the cycle, and our breath tapers off at the end. During ujjayi, keep the same rate of breath flowing at all times, from start to stop. This requires that you make the second half of each inhale or exhale stronger to balance the flow. Fill yourself with the breath from bottom to top as in full yogic breathing, creating lift in the spine and torso, and keep the lift as you exhale. Breathe smoothly and steadily, making your inhalation and exhalation even in duration. This type of breathing is very soothing to your nervous system and promotes calmness and peace of mind.

Alternate Nostril Breathing This type of yogic breathing is called nadi shodhana. As described earlier the word nadi means “energy channel” and shodhana means “cleansing.” Nadi shodhana breath is designed to cleanse the nadis. You will recall that there are three main channels in the body for prana: one central (sushumna), one right (pingala), and one left (ida). Usually there is a difference in the energy flow between the right and left channels that shifts back and forth during the day. You can notice this by the difference between your left and right nostrils as you breathe. One side will be dominant for a while, and then the pattern will reverse. The alternating breath of nadi shodhana both cleanses and balances the flow between ida and pingala.

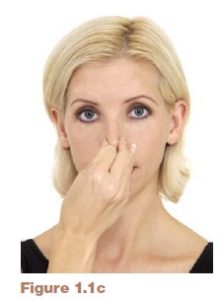

Alternate nostril breathing requires a little technique for regulating the breath through one nostril at a time. To experience this technique hold out your right-hand palm, face up. Curl your index and middle fingers to touch the fleshy part of your palm at the base of your thumb. Keep your thumb extended and free (figure 1.1a). You will use your thumb to close off your right nostril and your other two fingers to close off your left nostril.

The technique for nadi shodhana is as follows:

- Put your right hand into the form just described. Begin with a deep inhalation.

- Close your left nostril with your ring finger and exhale fully through your right nostril (figure 1.1b).

- Inhale fully through your right nostril, close your right nostril (using your thumb) as well, and pause (figure 1.1c).

- Open your left nostril, exhale fully through the left side, and pause (figure 1.1d).

- Inhale fully through your left nostril, close your left nostril as well, and pause. Open your right nostril and exhale fully through the right side.

- Repeat this pattern for a few minutes, then finish with inhalation through your right nostril and exhalation through both nostrils. Return to natural breathing.

What to Wear

When you practice hatha yoga the most important thing about clothing is that it be comfortable and functional. Your clothing should not restrict your movements and should be appropriate for the temperature of the room in which you practice. It is essential to remove socks and shoes when practicing yoga so that your feet will stick to your yoga mat and your feet and toes will be able to expand.

For public yoga classes that use alignment principles it is important to wear clothing that allows your teacher to see your alignment. For instance, long, baggy pants do not allow the teacher to see if your leg muscles are properly engaged or if your knees are properly aligned. And if you are trying to learn to properly engage your shoulder blades on your back you will need visibility there. For these classes tights and leotards are recommended for women, shorts and tank tops for men. For classes that do not emphasize alignment, you can have fun wearing the latest in yoga apparel to class. For restorative and gentle classes the more comfortable you are, the better. In general, your clothing should support your practice, be comfortable, and be fun.

How to Use Props

The most important piece of equipment you will need to start your yoga practice is a good yoga mat. A yoga mat provides a nonslip surface that will keep you steady as you move into and out of various postures. There are many different types of mats available. It is best to choose a good-quality mat that supports your practice. The thinnest mats (about 1/8 inch thick) are rubberized, colorful, and provide a good nonslip surface; however, these mats do not provide much cushion for bony protrusions when you are doing floor exercises. The thickest mats are called transformer mats. These mats provide excellent cushion and nonslip characteristics though they are quite heavy and expensive. It is a good idea to use the mats your yoga studio provides for a while until you decide what type is best suited for you.

There is a variety of other props that will support your practice as well. A good yoga blanket is a must for the beginning student. Most studios provide blankets so that you do not have to purchase your own. The best blankets are of the Mexican close-weave variety. These fold with crisp, clean edges and provide the most stable support. Synthetic, loose-weave blankets or towels do not provide stable support.

Yoga blocks, straps, bolsters, sandbags, and eye pillows are also useful props when called for by your teacher or in the asana descriptions. Most studios provide all of the props for no charge except mats, which can usually be rented for a small fee per class. Eye pillows are usually purchased separately.

Yoga blankets placed under your hips provide extra cushion and lift to help you keep your low back from rounding when you’re sitting on the floor. Straps provide extra reach when you are extending your legs and reaching for your toes as well as support for some sitting and partner postures. Yoga blocks can be placed under your hands in side and forward bends until you can reach the floor without them. Blocks can also be squeezed between your thighs in some postures to teach proper engagement of the legs. Sandbags provide weight for extra grounding for floor exercises. They can encourage relaxation when placed on your body because they give a safe, stable pressure. Eye pillows are very calming for restorative postures and final relaxation. They provide a gentle, even pressure on your eyelids.

Where to Practice

The great thing about your yoga practice is that it is truly portable. You may decide to practice yoga at places and times other than just public classes. If you are away from home, and depending on the level of your practice, you may decide to practice in an airport during a layover (headstands are great conversation starters), in a hotel room (after moving the furniture), or at work in a vacant conference room.

You may want to create a special space in your home for your practice. A room with a hardwood floor or smooth tile is ideal. A low-pile carpet can also make a good surface for yoga practice if you use a good yoga mat to help you avoid slipping. Yoga mats are now widely available in locations ranging from yoga studios to grocery stores.

When to Practice

The most important aspect of when you choose to practice is that you are regular and consistent in your practice. The more you practice yoga the more you will progress. Allow yourself one or two days off per week to give your body time to recover, as needed. If you are menstruating or ill be willing to take a few days off for that as well. In general it is best to commit to practicing daily for a set amount of time, even if you cannot practice at the same time each day. Choose a time that fits your schedule when you will not be distracted by other things. Figure out how much time you can give to your yoga practice each day. Even if you practice as little as 15 to 20 minutes a day you will notice improvements in your strength and flexibility and in the way you feel. As you progress you can add to your practice time in preparation for a full-length public class (typically 90 minutes long).

If you practice in the morning you may notice that your mind is keen but your body is a little sluggish. In the late afternoon or early evening your body is usually flexible but your mind may be tired and lacking focus. The body and mind are usually at their peak in the late morning and early afternoon, so those are optimal times for a full asana practice. There are many studios and class times available in most cities and towns, so you should be able to find a time that works for you.

You should not practice yoga when you have a fever. Yoga raises the body temperature and competes for the energy your body needs to recover. Likewise, do not practice if you are weak from cold or flu, except to do restorative postures. Women should avoid doing inversions such as headstand or shoulder stand when they are menstruating. This is because the healthy downward flow of the menses is disrupted if a woman inverts during this time. A woman can substitute a supported Downward- Facing Dog or Legs-Up-the-Wall pose in this case.

Always seek the advice of your physician and your yoga instructor about practicing if you are ill or injured. A yoga instructor who is skilled in the art of yoga therapy can help you greatly if you are injured. But be sure that your teacher has been properly trained in yoga therapy. A school of hatha yoga that is respected for yoga therapy is Iyengar Yoga.

When you are ready to attend public yoga classes, it is recommended that you attend at least twice weekly in order to progress in your practice. This site provides excellent training to prepare you for your first class and can remain an outstanding reference for you as you progress in public classes and deepen your own home practice.

What and When to Eat

There are a few general guidelines to follow for eating before yoga practice, such as finish meals three to four hours before an intense practice. It is best if the digestive process is complete before you practice yoga, because digestive muscles compete with other body muscles for blood after you eat. If you have low blood sugar or have little time between yoga sessions for a meal you can supplement with fruit, energy bars, or yogurt anywhere from 30 to 60 minutes before class. Protein smoothies also make an excellent quick meal when time is short, because liquids are more easily digested.

For some schools of hatha yoga the issue of vegetarianism is a serious concern, while for others it hardly receives mention. Disagreements on the morality of what we eat can result in heated confrontations within and outside of the yoga community. For most of us the way we eat is a deeply personal issue. For many it is also an issue of how we treat the other beings on our planet.

Arguments against a diet including meat are usually based upon the concept of ahimsa from Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. There are many levels of interpretation of this principle. Some define ahimsa as nonviolence and take the stance that taking any form of life to further your own is a violent act. Some yoga practitioners go so far as to wear masks and sweep the ground in front of them to avoid taking the lives of insects.

Others interpret ahimsa as noninjury and view the world as inherently containing acts of violence, such as cutting the umbilical cord on a baby or defending your self or loved ones from attack. If violence cannot be avoided in an engaged life, the injury it does can be skillfully managed. For this school of thought it is not the act itself that is important, it is the intent behind the act. The main measure of an act is whether or not it is shri, or life-affirming. For example, chemotherapy is a very violent act against the body, yet the intent is to save the life of the patient.

For others the choice of how to eat is primarily a matter of health and happiness. Certain types of diet are healthier than others and directly affect the quality of your life. Most people who practice yoga find that they are more aware of how their bodies feel and how their diet affects their bodies. As we increase our sensitivity to the gift of our body we are likely to move naturally toward the best choice for ourselves.

Learning to Meditate

Meditation is the basis for all inner work. It is the direct naked encounter with our own awareness that shifts our understanding of who we are and gives us the power to stand firmly in our own center. No one else can do this for us. Only meditation can unlock these doors. Swami Durgananda (Sally Kempton), The Heart of Meditation

Meditation is an important part of the journey inward. It is a gateway into your experience of your own inner nature of divinity. Many great yogis have followed the pathway of union with the self through meditation. A strong and supple body greatly enhances your experience of sitting meditation. Many Westerners are not aware that the postures of hatha yoga were originally created to prepare the body for sitting meditation.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras call for meditation, or dhyana, as the seventh stage of the eight-stage path to enlightenment. Once students have mastered the sixth stage (concentration, or dharana), they may proceed to meditation. But almost everyone begins their meditation practice while they are still working to increase their ability to concentrate, so do not be discouraged as you observe your mind wandering. That is normal.

The dictionary defines meditation as a devotional exercise of contemplation. The root Latin word for meditation, meditari, means “to think about or consider.” Any form of contemplation can be a meditation if you are focused clearly on the issue at hand. For instance, time you spend considering how you want to live and who you want to be in this life are excellent examples of meditation. Even if you are confused about your course of action, meditation can connect you to your heart, where there is a deep knowing about the right choices. The more you meditate, the more you will learn to trust your own inner source of guidance.

It is not necessary to meditate if you practice hatha yoga. Nor is it a requirement to practice yoga if you want to meditate, but combining the two practices can enhance your experience of both.

Ways to Meditate

There are many ways to meditate, just as there are many styles of yoga. The best way to determine the best style of meditation for yourself is simply to try several styles and see which one says yes to your heart.

The first stage of meditation is to focus clearly on a specific object or sensation with your eyes open or closed. You can repeat a word or phrase, visualize a place, object, or deity, or simply tune in to your breath and observe it slowly coming in and going out.

Sound meditation usually involves the use of a mantra to draw you into deep states of awareness, as described in the “Paths of Yoga” section of this article. A mantra is a sacred utterance or sound charged with psychospiritual power. It is usually a word or phrase honoring a particular deity or aspect of the divine. Yogis use mantras to achieve deep states of meditation and to invoke specific states of consciousness, and they believe that a mantra expressing a particular aspect of the divine will help to awaken that aspect of their own consciousness. A mantra is used to help awaken that part of our personalities that can overcome the obstacles in our lives. The most recognized and important mantra is the sound OM. Silently repeating your chosen mantra as you sit in meditation can be very powerful.

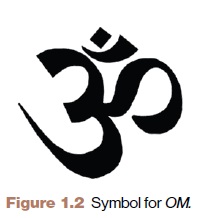

The OM was considered the single most important sound in chanting of the Vedas. The symbol for OM, illustrated in figure 1.2, represents all the states of human consciousness and is interpreted as follows. The bottom curve represents the dream state, the upper curve represents the waking state, and the middle curve, or swirl, to the right represents the deep, dreamless sleep state. The crescent shape (top right) represents the veil of illusion, or maya, and the dot represents the transcendental state.

For some people, visualization meditation may be more effective. You can visualize your chosen deity—a god or goddess or a peaceful nature scene, such as a flower or a beautiful coastline. The image you choose should elicit feelings of deep contentment for you.

Another popular meditation technique is simply to focus on your breath. There is no attempt to control or change the breath. Just focus on all aspects of your breath- ing—how your chest lifts and your abdomen expands and how the air feels moving through your nostrils. There is no judgment, no good or bad aspect of the breath, just awareness. The breath is a manifestation of the divine energy that animates your body. This meditation helps bring to consciousness the awareness that you are being breathed by that divinity.

Heart-centered meditation involves focusing on your heart center and the feelings and sensations that arise there. Focusing on our hearts takes us deeply into our core awareness and our most profound feelings of love and joy. You can visualize the breath moving directly into your heart center to begin to connect with these feelings.

Where to Meditate

You must have a room, or a certain hour or so a day, where you don’t know what was in the newspapers that morning, you don’t know who your friends are, you don’t know what you owe anybody, you don’t know what anybody owes you. This is a place where you can simply experience and bring forth what you are and what you might be. This is the place of creative incubation. Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth

The place you choose for your meditation is important. It is the way you honor both your meditation ritual and yourself. Select a sacred space to support your meditation practice in a way that honors the things that have meaning for you. You may choose a space filled with light and fresh air or one that is cozy and warm. The most important thing is that your space helps to transport you to that sacred place within yourself.

Also, it is powerful to come back to the same place each time you sit for meditation. Your continued practice will build the energy in your space, establishing a strong, peaceful vibration. The ideal space is a room with no other purpose (except possibly your hatha yoga practice). If it is not possible to set aside a whole room just for meditation, select a corner of a room that is free from distraction.

It is a wonderful practice to create an altar in your meditation space. An altar can transform your mediation space, because it creates a sense of ritual. And ritual can take you right into your heart, because it serves to remind you of what is important. Your altar can be anything you want it to be as long as it is something that matters to you. There are no rules, so be creative. Some items you might use on your altar are candles, incense, pictures of teachers or others you look up to, and pictures of deities or great beings. These items will uplift your senses and establish a pure energy. Flowers can be an offering to your favorite deities or can simply invite your heart to open.

When to Meditate

The best times to meditate are just before sunrise and at sunset. These are the times when nature slows her activity, birds are quiet, and animals do not stir. Because we are connected with the natural world our minds and bodies are also still at these times, yet we can remain alert. As often as possible, practice your meditation at the same time each day. Consistency builds a strong and useful meditation practice.

Your meditation practice can be an excellent complement for your asana practice. If you begin or end your practice with 5 to 10 minutes of meditation you will find that both practices benefit. However you do it, it is recommended that you create a regular meditation practice. Even 5 to 10 minutes each day will show positive results in your state and clarity of mind.

Positions for Meditation

The Classical position for meditation is sitting on the floor in a cross-legged position. The sitting positions are chosen because they allow the meditator to sit comfortably for relatively long periods. A common meditation asana that allows for extended sitting (20 to 90 minutes) are the sage positions (siddhasana). If you are unable to sit in one of these positions, you can meditate sitting with good posture in a chair.

Proper alignment when you sit will help to make your experience more enjoyable and productive. Begin your meditation by either practicing one of the techniques just described or a technique of your own choosing. It is a good idea to set a timer to let you know when your allotted time has passed to avoid the distraction of watching the clock.

Mudras

A mudra is a hand gesture, an asana for the hands. Throughout history, hand gestures have been used by all civilizations and religions. The priests and priestesses of ancient Egypt used hand gestures to perform prayer rituals 5,000 years ago. People of many cultures have used them, including the Aborigines, Romans, Turks, Persians, Africans, Chinese, Gigians, Mayans, and Native Americans. Christians will recognize specific hand gestures in the portrayals of Jesus, though few know the significance of these mudras. The most commonly recognized mudra is the “prayer” mudra, known to yogis as anjali mudra. Anjali means “offering”—this mudra can represent offering to one’s self in service or in gratitude. In India mudras became very important with the practices of yoga.

The word mudra means “seal,” because the mudras create an impression in the subtle body like a letter sealed with a hot-wax imprint. The impressions are made in the energy body and, therefore, are used to control the flow of life energy in the body. This life energy, or prana, radiates from the fingertips. Each finger conducts a different vibrational energy, and these finger postures bring the energies together in different combinations. Each combination completes an energy circuit in the body and mind, creating a calming effect that also stimulates various chakras. There are many combinations of finger postures to encourage different kinds of mental focus. Because of the effect on the chakras, mudras may also be helpful in healing various medical conditions. Kundalini yoga and other modalities use mudras for this purpose.

These are some of the most commonly known yoga mudras:

Adi mudra: Adi means “first,” and adi mudra is the first position in which an infant holds its hands—making a fist with the thumb tucked inside. Adi mudra is used to control clavicular (upper-chest) breathing. It stimulates the deepest recesses of the brain, that organ which is most closely associated with the crown chakra.

Abhaya mudra: The “gesture of fearlessness” for dispelling fear in others. This mudra is shared and understood equally by Native Americans, Hindus, Buddhists, and the Christian painters of the Renaissance. When you raise your right hand, extending your fingers straight up and holding your palm open, you are showing peaceful and compassionate intent. This mudra relates to the anahata (heart) chakra.

Agni mudra: Agni means “fire,” which in yoga is commonly associated with the digestive process. In agni mudra the thumb touches the tip of the middle finger; the first, third, and fourth fingers are extended away from the palm. Agni mudra improves both digestion and intelligence, and is good for the manipura (abdomi- nal) chakra.

Apan mudra: Also known as the “deer mudra” because of the antlerlike pointing of the index and little fingers. Apana refers to the cleansing effect of prana when it flows down and out of the body. In this mudra the tip of the thumb contacts the tips of both the second and third fingers; the first and fourth fingers point upward like the antlers of a deer. It promotes a patient and serene state of mind.

Gyana mudra: This mudra is accomplished by touching the tip of the thumb and index fingers together. The second, third, and fourth fingers are extended away from the palm. This is the most popular mudra for meditation, as it promotes calmness and clarity of mind.

Dhyana mudra: Dhyana means “meditation.” The hands are placed palms up in the lap, right on top of left, with the tips of the thumbs touching. Some of these mudras are used with the asanas.

Leave a Reply