Studies show that, on average, vegans consume a little less than 30 percent of their calories from fat. That’s a bit lower than the average for non-vegan Americans, but not by much. The big difference is in the type of fat that vegans consume since plant foods are much lower in saturated fat than meat, dairy, and eggs.

Studies show that, on average, vegans consume a little less than 30 percent of their calories from fat. That’s a bit lower than the average for non-vegan Americans, but not by much. The big difference is in the type of fat that vegans consume since plant foods are much lower in saturated fat than meat, dairy, and eggs.

The term “fat” is a big category that includes a number of different fatty acids, two of which are essential to our diet. Actual requirements for essential fats are low, but there may be advantages to eating some fat-rich foods overall. In this chapter, we’ll look at three issues: the long-chain omega-3 fats, meeting essential fatty acid needs, and the question of how much fat vegans can safely consume.

Long-Chain Omega 3 Fats

EPA and DHA are the “long-chain” omega-3 fatty acids that are found mainly in cold water fish. These fats are thought to be important for cardiovascular disease primarily because they reduce blood clotting and inflammation.1 Because DHA is found in nerve tissue, inadequate levels could also be linked to neurological problems such as dementia and depression.

Since the long-chain omega-3 fats are found primarily in fish and to a much smaller extent in eggs, lacto-ovo vegetarians consume very little, and vegans generally have none in their diets (although some vegans may consume very small amounts of EPA from sea vegetables). Whether or not this matters is a big question in vegan nutrition.

Potential Benefits of DHA and EPA: The Science behind the Claims

A number of studies (and large reviews of studies) have suggested that omega-3 fats reduce the risk of heart disease, but others have found no benefit. There has been so much published on this subject that it makes it almost impossible to analyze the individual studies. We need to rely on systematic reviews and meta-analyses instead. But even the reviews have been conflicting; two large ones published in 2006 reached opposite conclusions. When research is this inconsistent, it probably indicates that the benefits are modest at best.

Although the omega-3 blood levels of vegetarians have been measured often enough to show that they are clearly lower than in fish-eaters, the actual effects of these lower levels aren’t clear. A 1999 study in Chile found that vegetarians had significantly more platelets (which are involved in blood clotting) and a shorter bleeding time than non-vegetarians. This suggests greater blood-clotting activity, which could raise heart disease risk. But when the vegetarians were supplemented with EPA and DHA for eight weeks, the bleeding time stayed the same (although other factors changed).

In a 1992 study in the United Kingdom, there were only small differences between vegetarians and non-vegetarians in factors that affect blood clotting, and bleeding times were similar.

So, of two studies looking at these effects, vegetarians fared worse than meat-eaters in one but were largely the same in the other. We need a lot more information before we can draw firm conclusions. Whether these lower omega-3 intakes increase risk in vegetarians for autoimmune diseases (which are affected by inflammation) or depression or dementia hasn’t been studied, but right now there is no strong evidence that they do. And people who eat seafood but not other meat don’t appear to be at lower risk for death from heart disease than vegetarians.

Omega-3 Fats In Plants

While plant foods don’t have DHA and EPA, a few provide alphalinolenic acid (ALA). This is a short-chain omega-3 fat that is essential in diets and technically can be converted to EPA and DHA. It’s found in flaxseeds, hempseeds, chia seeds, canola oil, walnuts, soy oil, and some soyfoods.

A second fatty acid called linoleic acid (LA) is also essential in the diet. This is an omega-6 fat and it’s abundant in commonly consumed oils like safflower and sunflower oil as well as whole plant foods. Americans, including vegans, get plenty of this essential fat.

The problem is that high intakes of the omega-6 fatty acid LA suppress conversion of ALA to DHA and EPA. Experts suggest that for optimal production of DHA and EPA, diets should contain no more than a 4 to 1 ratio of LA to ALA. But the ratio in vegan diets is more typically around 15 to 1.9 That is, vegans are consuming too much of the omega-6 fatty acid LA and sometimes not getting enough of the omega-3 fat ALA. As a result, dietary strategies to boost ALA intake and lower LA intake have become popular among some vegans. But do they work?

Unfortunately, there are no long-term studies looking at blood levels of EPA and DHA in vegetarians when these strategies are used. And short-term studies indicate that it takes large amounts of ALA to increase the amount of DHA in the blood. In fact, for the most part, studies using supplements or food sources of ALA have been largely unsuccessful in raising levels of DHA and only moderately successful in raising levels of EPA.

In addition, it’s not clear that high doses of the short-chain omega-3 s are completely benign. In the Nurses’ Health Study, higher intakes of ALA were linked to eye problems, including increased risk of macular degeneration.10 In contrast, the highest intakes of DHA tended to be protective of eye health. These studies were done on only one population by one group of researchers, and the biggest contributors of ALA in omnivore diets are dairy and other animal products, not plant foods. So it’s not clear whether these findings are relevant to vegans. The findings suggest caution regarding high intakes of ALA, but more information is needed before we should draw conclusions.

Based on the little we know, it’s not clear that large amounts of ALA are safe. Nor is it clear that increasing ALA intake boosts blood levels of DHA and EPA. But there is another option for vegans: algae-derived DHA and EPA supplements.

DHA Supplements

Fish get their DHA from algae, and vegans can go to the same source. Preliminary research suggests that a supplement providing 200 milligrams of DHA per day for three months can raise blood DHA levels in vegans by as much as 50 percent. Other studies of vegetarians (not necessarily vegans) have also shown the positive effects of taking DHA supplements.

But because the research on the overall benefits of omega-3s is so conflicting, it’s hard to know whether these supplements are useful for vegans. We are not convinced that they are. On the other hand, we are not convinced that the lower blood levels of DHA and EPA in vegans is unimportant. Until we know more, we are inclined to recommend supplementing with very small amounts, around 200 to 300 milligrams of DHA (or DHA and EPA combined), every two or three days.

Many vegan supplements provide only DHA, but new ones providing both DHA and EPA are becoming available. A few vegan foods such as soymilk, energy bars, and olive oil are also fortified with algae-derived DHA.

Meeting Essential Fatty Acid Needs

While large intakes may not be advisable, everyone needs to consume some ALA since it’s an essential fatty acid. Recommended intakes of ALA for adults are 1.1 grams per day for women and 1.6 grams for men. Meeting those needs isn’t difficult, but it requires a little bit of attention since ALA is not widely available in foods.

Each of the following provides around one-quarter of the daily ALA requirement for an adult male or one-third the requirement for an adult female. To meet the ALA needs of an adult woman, choose three servings from these foods, and for an adult man, choose four.

1 teaspoon canola oil

1/4 teaspoon flaxseed oil (just a few drops)

2/3 teaspoon hempseed oil

1 teaspoon walnut oil

2 teaspoons ground English walnuts or 1 walnut half 1 teaspoon ground flaxseeds*

1/2 cup cooked soybeans

*Don’t use whole flaxseeds since they aren’t well-digested and the ALA is poorly absorbed.

1 cup firm tofu

1 cup tempeh

2 tablespoons soynuts

How Much Fat Should Vegans Consume?

Despite the popularity of vegan diets that eliminate all high-fat foods, there hasn’t been much research comparing very low-fat vegan diets to those that include some higher-fat plant foods. And there is reason to think that very low-fat vegan diets are not ideal. Eating diets that are too low in fat could be the reason that some people abandon vegan diets and return to eating meat. Many think of meat as “protein,” forgetting that these foods are also typically high in fat. People who don’t feel well on vegan diets sometimes add meat back to their diet because they’re convinced that they aren’t getting adequate protein—when, in fact, they might have felt better by simply adding more fat to their menu.

Contrary to popular opinion, diets that include fat from plant foods are not linked to heart disease. (We’ll talk more about this in Chapter 13.) And the idea that high-fat diets are linked to cancer risk is weak. Most importantly, plant foods that are naturally high in fat are beneficial to health. There is a large body of research showing that nuts protect against heart disease. They are also rich in vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals. You’ll see in Chapter 7 that we recommend that all vegans include a serving or two of nuts in their meals every day.

Higher fat foods can also make it easier for vegan children to meet calorie needs. And while it’s somewhat of a paradox, we’ll see in Chapter 13 that including some of these foods in weight-reduction diets can improve success.

These foods make vegan diets more interesting and easier to plan, which means that they make it more realistic for people to transition to a vegan diet and stick with it for the long-term. From both a practical and a health point of view, it doesn’t make sense to ban high-fat foods from vegan diets. And as we’ll see below, even oils can play a role in healthy vegan diets.

Fat in Vegan Diets: Practical Guidelines

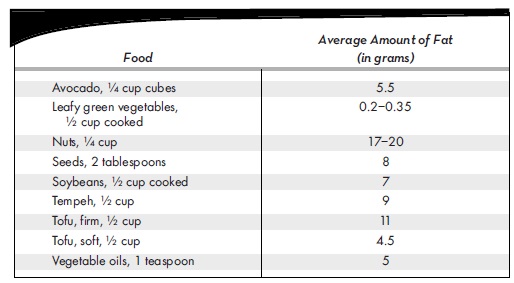

- Keep total fat intake in the moderate range. There is no consensus of opinion among experts on the ideal level of fat in the diet. Excessive fat intake is not healthy, but that doesn’t mean that all fat is bad. The World Health Organization cautions against consuming a diet that is less than 15 percent fat for adults or less than 20 percent for premenopausal women.13 We recommend that vegans strive for a fat intake somewhere between 20 and 30 percent of calories. That means between 22 and 33 grams of fat for every 1,000 calories you consume. Here is a quick guide to approximate amounts of fat in plant foods:

- Avoid fats that are associated with chronic disease risk. But both saturated fat and trans fats may raise the risk for heart disease and diabetes and could be associated with cancer risk as well. Generally speaking, vegans don’t need to worry since both tend to be low in plant-based diets. Watch for labels that include “partially hydrogenated vegetable oil,” a type of fat that is high in trans fats.

- Limit intake of oils high in the omega-6 fat linoleic acid. These include corn, soy, safflower, sunflower, and to a lesser extent, peanut and sesame oils. Watch for prepared foods that include these oils toward the top of the ingredient list.

- Get most of your fat from foods that provide monounsaturated fat. Best sources are nuts, nut butters, avocados, and olives, and olive, canola, or high-oleic safflower and sunflower oils.

- Be sure to meet your needs for the essential omega-3 fatty acid ALA. Follow the guidelines on page 55 to make sure you’re getting enough of this fat.

- Consider taking a DHA supplement. Vegans over the age of sixty, especially, should consider taking a DHA (or DHA plus EPA) supplement of 200 to 300 milligrams a day. Younger vegans might consider taking this much every two to three days.

Vegetable Oils In Vegan Diets

You don’t have to include vegetable oils in your diet, but they can fit into a healthy vegan eating plan. Not all vegetable oils are equal, though. Since vegans tend to have a high ratio of LA to ALA in their diets, it’s a good idea to choose oils that are low in LA. Another consideration is the smoke point of oils. Oils with a low smoke point begin to break down at high temperatures, producing potentially toxic compounds. Smoke point is affected by the type of fatty acids in the oil as well as processing. Oils with a higher monounsaturated fat content have a higher smoke point, which makes them better for cooking. Cold-pressed or unrefined oils have a higher percentage of protective phytochemicals, but they also have a lower smoke point, so they are better to use in dressings than for cooking.

For baking and cooking, choose these oils most often:

- Extra virgin olive oil: All types of olive oil are high in mono-unsaturated fats, but extra virgin olive oil also contains compounds that may protect against heart disease, cancer, and stroke. Its smoke point is only moderately high, so use it only for sauteing foods at lower temperatures or for cold or warm salads.

- Canola oil: It is high in monounsaturated fats and has a somewhat higher smoke point than olive oil.

- High-oleic sunflower or safflower oils: These are special hybrids grown to produce an oil that is rich in monounsaturated fat. They must say “high oleic” on the label.

- Almond, avocado, hazelnut, and macadamia nut oils: These are all rich in monounsaturated fats, and their high smoke points make them a good choice for cooking. They tend to be expensive, but you may want to splurge on them occasionally for special dishes.

Minimize these oils in your diet:

- Corn, soybean, safflower, and sunflower oils (unless labeled as “high oleic”). These are popular for frying because they have high smoke points. But all are high in the omega-6 fatty acid linoleic acid (LA) and should be minimized in the diet. Anything labeled “vegetable oil” is almost always soybean oil.

- Peanut and sesame oils: These are moderately high in mono-unsaturated fats and have a relatively high smoke point, but both—particularly sesame oil—have a fairly high LA content.

Use these oils only as supplements:

- Flaxseed and hempseed oils: Because of their very high ALA content (especially for flaxseed), these oils are generally used in small quantities as a supplement—perhaps sprinkled over vegetables. They have low smoke points and should never be heated.

What About Coconut Oil?

Packed with saturated fat—it has more than either butter or lard— coconut oil has developed a surprising reputation as a health food. This is partly because some research has shown coconut oil to have antimicrobial properties. Also, the main fat in coconut oil, which is called lauric acid, raises good HDL cholesterol, producing a favorable cholesterol profile. Virgin coconut oil contains a number of protective phyto-chemicals as well and, for people eating healthy diets containing plenty of fiber-rich plant foods, coconut oil consumption isn’t associated with heart disease. Cooks may like it for its appealing flavor as well as the fact that it is particularly stable and doesn’t turn rancid easily. It can also be useful when you need a solid fat for cooking. But the jury is still out on the health effects of coconut oil, so, like all added fats, it should be used in moderation.

Leave a Reply