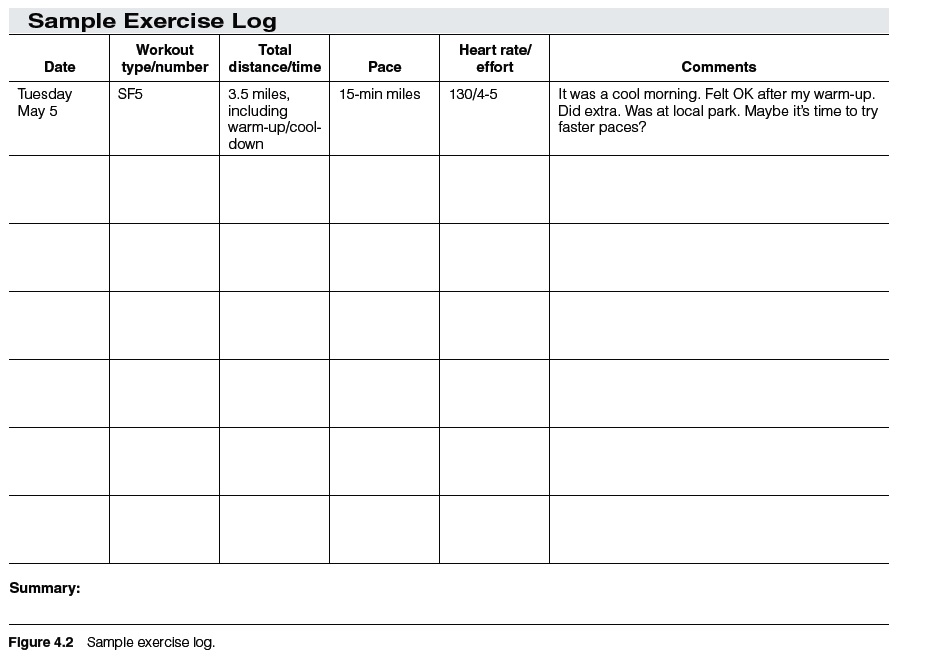

As you head out the door, you may want to determine how fast you’re going, how far you’re going, how many calories you’re using, and if you’re walking hard (or easy) enough. You should start a workout log so you can monitor your progress. Use the Figure 4.2 as a template.

Determining Your Pace

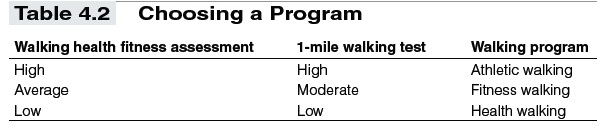

To decide what distances you can walk and at what speed, look back to the assessments in chapter 1. Your answers for the walking fitness assessment placed you in one of three groups: high, average, or low. Now cross-check that rating with your result in the walking health/fitness assessment, also in chapter 1, where you paced off a quick mile. Your time ranked you in one of three classifications, from high (athletic walking) to low (health walking).

A high rating in the first assessment will most likely correspond with a high rating in the walk, an average will match up with a moderate in the walk, and a low rating will match up with a low in the walk. If your results were this clear- cut, the following table shows you which walking program will be right for you (see table 4.2). But if the two didn’t mesh so neatly, use your rating for the 1-mile walk to guide you into a walking program. Your mile time demonstrated what you can do when you’re putting one foot in front of the other.

Remember, however, this is only a guide. If you find yourself on the border between levels, be conservative to start and follow the easier program. Gradually explore the more intense workouts until you find what’s right for you for the long term. Feel free to mix and match workouts if you find yourself somewhere in the middle. That’s the beauty of five categories of workouts with a wide range of levels—there will be workouts to match every variation in personal fitness levels and daily energy swings. Always listen to your body. A complete and accurate assessment also includes internal feedback. If your ranking places you in the athletic walker category, but you have no desire to move that fast, then move back to a more moderate program. The same goes for those ranked in the moderate level; step back to an easier program if that will fulfill your walking wishes and help you achieve your health goals.

Remember, however, this is only a guide. If you find yourself on the border between levels, be conservative to start and follow the easier program. Gradually explore the more intense workouts until you find what’s right for you for the long term. Feel free to mix and match workouts if you find yourself somewhere in the middle. That’s the beauty of five categories of workouts with a wide range of levels—there will be workouts to match every variation in personal fitness levels and daily energy swings. Always listen to your body. A complete and accurate assessment also includes internal feedback. If your ranking places you in the athletic walker category, but you have no desire to move that fast, then move back to a more moderate program. The same goes for those ranked in the moderate level; step back to an easier program if that will fulfill your walking wishes and help you achieve your health goals.

Retake the 1-mile timed walk test every month or so to see how you’re progressing and to gain the confidence to pump up your program.

Table 4.2 Choosing a Program

Assessing Your Heart Rate

Over the years, formulas to assess appropriate workout heart rates have come under incredible scrutiny. Recent research investigates the accuracy of simplistic formulas such as the one that follows. The bottom line is, no mathematical formula will provide an exact workout heart rate. They are all estimates, at best, a starting point for getting to know your body and what feels good or not so good. I won’t take sides in the heart rate battle but instead give you a couple of formulas. Plug your data into both to see how they compare.

Simple Formula

If you’re a man, subtract your age from 220:

220 – age = maximum heart rate (max HR)

Then multiply your chosen goal or intensity by the result. For example, a 40-year-old man undertaking a moderate workout would follow this formula:

220 – 40 = 180 (max HR) * 70% (lower end of moderate range) = 126

180 * 79% (upper end of moderate range) = 142

Therefore, his target heart rate range for moderate workouts is 126 to 142, with the exact target depending on the workout selected.

Women use a similar formula, substituting 226 for 220:

226 – age = max HR

Then multiply your chosen goal or intensity by the result. For example, a 30-year-old woman who intends to do a moderate workout would follow this equation:

226 – 30 = 196 (max HR) * 70% (lower end of moderate range) = 137

196 * 79% (upper end of moderate range) = 155

This woman’s target heart rate range for moderate workouts is 137 to 155, with the exact target depending on the workout selected.

Resting Heart Rate Formula

The formula using resting heart rate (RHR) is the same as the simple formula, except it subtracts your resting heart rate after you subtract your age and then adds it back in later. This of course only works if you know your resting heart rate. Guessing isn’t good enough. Determine your resting heart rate by taking it before you get out of the bed in the morning—before you’ve been active or moving around much and before you’ve been jolted by the screech of an alarm clock. It can still be difficult to obtain, but give it a whirl. Highly trained athletes can have resting rates in the 30s and 40s! The rest of the population will be in the 50s to 70s, depending on condition, drugs that lower or raise heart rate, and disease.

If you’re a man, subtract your age from 220 to get your max HR, then sub- tract your RHR:

220 – age = max HR – RHR = max HR II

So, for a 40-year-old man, the formula would work like this:

220 – 40 = 180 (max HR) – 60 (RHR) = 120 (max HR II)

120 * 70% (lower end of moderate range) = 84 + 60 (RHR) = 144

120 * 79% (upper end of moderate range) = 95 + 60 (RHR) = 155

Therefore, if this man’s RHR is 60, his target heart rate range for moderate workouts is 144 to 155, with the exact target depending on the workout selected. Note that these are a bit higher than those using the simple formula.

Women use a similar formula, substituting 226 for 220:

226 – age = max HR – RHR = max HR II

So, for a 30-year-old woman, the formula would work like this:

226 – 30 = 196 (max HR) – 60 (RHR) = 136 (max HR II)

136 * 70% (lower end of moderate range) = 95 + 60 (RHR) = 155

136 *79% (upper end of moderate range) = 107 + 60 (RHR) = 167

Therefore, if this woman’s RHR is 60, her target heart rate range for moderate workouts is 155 to 167, with the exact target depending on the workout selected. Note that these are a bit higher than those using the simple formula and also higher than the man’s because women’s heart rates are usually faster because they are smaller.

Other Formulas

By no means are these the only ways to calculate a heart rate. If you read popular magazines, you’ll see variations popping up all the time. They can be fun to experiment with to see how different they really are. In many cases the differences are so minimal that it comes down to splitting hairs, which is something advanced athletes like to do! The previous two formulas should give you enough of a range to start you off on the right foot.

Again, these calculations are only estimates; individuals vary greatly. As you gain experience, learn to pay more attention to how you feel—your perceived exertion—than to your heart rate as you estimate how hard you’re working.

Rating Your Perceived Exertion

As you become accustomed to walking workouts, you’ll learn to read your personal perceived exertion level, which is another way to measure how hard you’re working without stopping to take a heart rate. Learning to gauge your exertion and to rate yourself requires listening to your body.

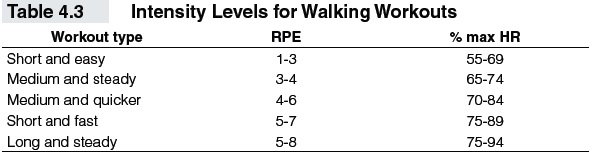

Measuring your rate of perceived exertion (RPE) can help you gauge how hard you’re working. Generally, a person’s sense of effort corresponds well to objective measurements such as percentages of maximum heart rate. An RPE of 1 to 3 has a corresponding heart rate of 55 to 69 percent of the maximum. A score of 4 to 5 has a corresponding heart rate of 70 to 79 percent of the maximum. A score of 6 to 8 has a corresponding heart rate of 80 to 94 percent of the maximum. Once they are highly trained, athletes can do short, intense workouts that push them to 10. The workouts in part II are arranged by type and progress in intensity as shown in table 4.3.

Speed is only one component that will affect your RPE. For example, if you walk with your dog, push a stroller, or carry some groceries, your walking speed may be decreased, but you will make up for some of this with the increased maneuvering difficulty, which will likely bump up your RPE a notch or two.

Table 4.3 Intensity Levels for Walking Workouts

Estimating Calories

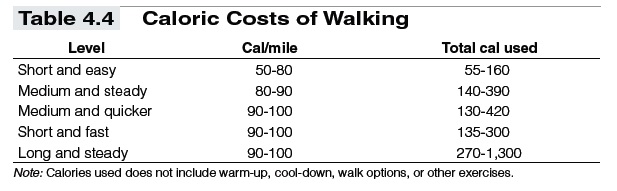

As your workouts progress in intensity or length, the number of calories you use also goes up. Even if weight loss is one of your fitness goals, don’t overdo your workouts with the goal to use more calories more quickly. Overloading your system too soon, at whatever level, can cause it to break down. With exercise, that means strains and pains that might put a stop not only to good exercise intentions but also to safe, gradual weight loss. Heed the tortoise’s wisdom: Slow and steady wins the race.

The number of calories you use in a workout is the least of your worries, really, because it’s usually not a huge amount. What counts is (1) teaching your system to use fat more efficiently as a primary fuel all of the time, which will decrease your body fat; (2) building muscle in place of fat, because muscle uses more calories than fat even at rest; and (3) letting your engine stay on high after a workout, as studies show it does. That means you’ll use more calories just sitting in your car, for example, once you’re more fit! And you’ll use more calories in the first minutes and hours after a workout even though you’re watching TV.

Be warned, too, that calorie expenditures vary greatly from person to person based on your individual metabolism, muscle mass, fat mass, and skill and fit- ness level. It also varies depending on the weather, terrain, and environment, as well as how hard you work during each workout. The estimates in table 4.4 are based on a 150-pound person. Add 15 percent to the totals for every 25 pounds over 150, and subtract 15 percent from the totals for every 25 pounds under But, remember, these are only estimates.

Table 4.4 Caloric Costs of Walking

Table 4.4 Caloric Costs of Walking

Estimating Distances

Many cities have trails that are marked every quarter mile, half mile, or full mile. These make setting up a walking routine pretty easy if you need to know or want to know distances versus time on your feet. If there are no marked areas, measure your courses by drive alongside your sidewalk route (remember, this is a very rough estimate), or buy an inexpensive pedometer or even a GPS (global positioning system) to measure your distance.

You can also do shorter workouts on a quarter-mile track. Once you get the feel of how fast you cover a certain distance, you can use time as your guide to measure distance. For example, walk 15 minutes one way, then 15 minutes back for a 2-mile round trip at a 4-mile-per-hour pace. Note that four laps around a track only in the inside lane is 1 mile; for every lane outside that, you’re adding a short distance. In the outside lane, four laps equal about 11⁄8 miles. Pay attention to etiquette when you use a track. The inside two lanes are reserved for serious runners and walkers doing specific timed workouts (intervals) geared toward higher performance. Unless you need to time every lap you walk, fit- ness walkers and joggers belong in the outside lanes.

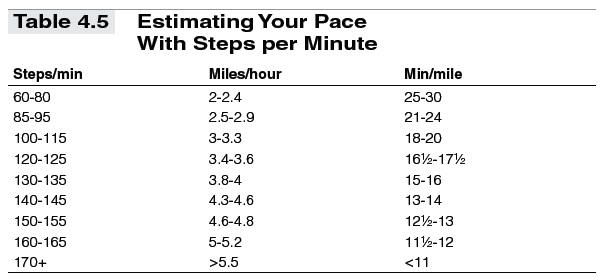

One more way to gauge your pace and distance is by counting how many steps you take per minute. Use table 4.5 as a guide. Remember, this too is only an estimate because stride lengths vary.

Table 4.5 Estimating Your Pace With Steps per Minute

Table 4.5 Estimating Your Pace With Steps per Minute

Counting 10,000 Steps

Perhaps you’ve heard about walking 10,000 steps a day to good health. Let me explain briefly what that’s all about. the suggestion to shoot for 10,000 steps is a great one because it addresses those looking for a little more movement as a part of their normal daily routine instead of a regular exercise program. the step count comes from an estimate that 1,000 steps is about 1 mile, so if you can attain 10,000 daily steps, you cover about miles in a day. these steps usually will not raise your heart rate into moderate training zones.

to achieve a goal like this, you should not immediately go from zero movement, or zero steps, to 10,000 steps but instead progress gradually. You can count your steps by wearing a pedometer.

Although the programs will improve your health like a step- counting program will, I also advocate adding general activity to your everyday life by taking the stairs or parking farther from your destination, activities that will help you reach the 10,000 steps goal. However, I also believe that if you are interested in fitness walking, you are interested in more structure and more focus on fitness training than counting steps provides. Of course, wearing a good pedometer can help you estimate workout distance. And it can be entertaining to see how many steps you normally take during your day.

Charting Your Progress

If you look at the black-and-white numbers of time and distance, then walking is one of many activities in which progress can be measured precisely. Measurement and log keeping are vital parts of any fitness program. But mental progress is also important.

The programs are founded on two promises from you, the walker:

- Honesty. You must always be true to yourself in assessing your personal ability, energy level, and needs, using only you as a yardstick, not a neighbor or friend. No workout is too slow, too short, or inadequate in any way. Every movement is a building block—accept it for what it is.

- Diligence. Sticking to it is essential. Don’t give up, no matter what. Fitness takes time, whether you’re going from a sedentary lifestyle to working out three days a week or from brisk walking to serious power walking. Your body needs time to adjust, to build muscle, to learn to use fat more efficiently, and to increase lung and heart strength.

What is progress in a fitness program? Progress requires looking over the edge into the unknown chasm of human potential and depth of character, then jumping. It is a process of exploring what your body can do, at whatever fitness level you choose, then trying it. It requires following your dream, step by step, until you can reach your goal.

Making exercise a regular part of your life takes at least six weeks and up to six months to become a real habit. For a beginner, making it to the six-month mark is true progress and worthy of celebration. For more intermediate and advanced walkers, putting in additional effort to advance further is progress. Exercise will become an inspirational activity that will alter your mood from bad to good, your stress from high to nonexistent. When I’m out of sorts or tired, heading out for a workout is often the best medicine, even if I don’t really feel like it. I almost always come back grateful that I pushed myself out the door. You will too.

Measurements must be made if you want to compare your workouts today with those from last week or last year. Make a copy of the training log in figure 4.2. Use it to record your workouts and keep track of your progress. Things to note in the comments section include the location of your workout, the weather, and how you felt. Evaluate your progress three ways:

- Time. You can retake the 1-mile walking test at any time (preferably not more than once a month) and compare your time with previous 1-mile walks. In your log book, observe how long it takes you to cover certain distances. Are you moving faster? Note if your workouts are becoming more challenging by getting longer. That’s progress, too.

- Feelings. You’ll notice a space in the sample log to jot down a couple of words about how you felt. Were your legs heavy or light? Were they sore? Did they feel relaxed? Did the workout feel easy or as if the whole thing were uphill even if it was flat? Maybe you’re going faster and farther, but it feels easier. All this relates to perceived exertion. Compare how you perceived your body during similar workouts in different weeks, as well as your rating of perceived exertion.

- Physical signs. Your body will let you know what’s going on—listen to it. Your resting heart rate is one concrete measure. Take it and record it often. As you gain fitness, your resting heart rate should go down. If it is suddenly higher than normal by 5 to 10 beats, that can signify overtraining, fatigue, stress, or an impending illness. Take heed and take a break.

If you’ve had your body fat tested (often available with calipers at clubs or using home versions that pinch your body fat at several specific sites), test it every month or two and note the changes. A scale is not a good judge because your body weight might stay the same or even go up, even though you lose fat and your clothes fit more loosely with consistent exercise. That’s because muscle weighs more than fat. What about your blood tests? Your blood cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels will likely go down. No matter what your body weight does, this is progress toward better health. Sleep pat- terns will also improve. You’ll fall asleep more quickly, rest more soundly, and awaken more refreshed when you exercise. You’ll also have more energy during the day.

You’re done just reading about walking for now. You’re ready to warm up, cool down, and dive into walking-specific stretching and strengthening exercises you can use before and after your workouts.

Leave a Reply